Other Stories

“Fr. McCabe and the Altar Boy”

by Bagún Glic

June 2010.

Fr. McCabe was very old and creaked audibly when he walked. He had served as a chaplain during the war and, for his bravery, was awarded the Military Medal. Perhaps it was the war that was responsible for the creaking. Rumour had it that there was still a bullet or a piece of shrapnel somewhere inside him. On top of that he was as deaf as a door knob, but that was probably just old age − he was very, very old. In spite of these physical deficiencies the parishioners of St. Aidan’s knew him as a good, kind man and a good priest – except when he forgot to turn up for a baptism or a wedding.

The altar boy was young, though not very young, and he knew all Fr. McCabe’s foibles. They made a good team, he thought, though it could be challenging at times. Altar boy training, for example. At that time the Mass was said in Latin and the first task in training an altar boy was to cram his little head with buckets of Latin responses. The beginning of Mass was particularly treacherous as a dozen Latin verses had to be recited alternately by priest and altar boy at breakneck speed. As Fr. McCabe was deaf he couldn’t hear his altar boy’s responses so he just kept going, regardless, and so did the altar boy. The trick, it seems, was to both finish at the same time so that the congregation, if there was one, would be unaware of the jumble.

| Introibo ad altare Dei Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meam. |

I will go in unto the altar of God Unto God who giveth joy to my youth. |

What beautiful prayers. Of course, Fr. McCabe’s altar boy knew little of their meaning. His job was to say them, not to admire them. Frostbitten fingers were quite common in our altar boy who cycled through the wintry early-morning air to get to St. Aidan’s, while the church itself was really just a large wooden hut with a corrugated-iron roof and no heating of any kind. Such fingers were a serious impediment to his putting on the long black cassock with its two thousand small buttons, so he was thankful for the three hundred which were missing around the knees. The cold must have been an impediment to the parishioners, too, as there was often no congregation. You see, Fr. McCabe and his altar boy preferred the quietude of the weekday Mass which was at 7:30 a.m., a trifle early for everyone – except, on occasion, for Mrs. O’Brien who was almost as old as the priest, who liked to sit at the back next to the organ, and who had once given the incredulous altar boy two silver sixpences which he spent on aniseed balls and liquorice.

| Confiteor Deo omnipotenti, beatae Mariae semper Virgine, beato Michaeli archangelo …quia peccavi nimis … |

I confess to almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the archangel …that I have sinned exceedingly … |

Perhaps “exceedingly” was overstating it for this particular altar boy or, indeed, for the vast majority of boys of his age. Still, the Confiteor was a part of the Mass and everyone had to say it. Not only had he to confess to the blessed archangel, but the poor altar boy had also to confess to Fr.McCabe in the confessional.

Are there not three conditions to be fulfilled by the penitent before absolution is given, namely: examination of conscience; an act of contrition; and a firm purpose of amendment? Should not a fourth condition be applied to the priest − that to be allowed to hear confession he should first be able to hear a bomb going off? Perhaps not. Although Fr. McCabe was as deaf as the knob on the door of the confessional, he could see the light streaming in when it opened and, after a suitable pause, would begin to mumble Latin through the grill. Although the altar boy had few sins to confess, he had to be quick about it or he would be given three “Hail Marys” and absolution before he was finished. He always came away a little disappointed on such occasions as he had been taught to value confession. One wonders how Fr. McCabe felt about it. Worse still were the times when the boy heard the chink, chink of coins as Fr. McCabe counted the collection money while he told him of fibbing and answering his mother back. But the altar boy did not condemn the old man. He liked him, even loved him, as a boy might love his granddad. Nor should we condemn him.

| Pone, Domine, custodiam ori meo, et ostium circumstantiæ labiis meis: ut non declinet cor meum in verba malitiæ, ad excusandas excusationes in peccatis. | Set a watch, O Lord, before my mouth, and a door round about my lips: that my heart may not incline to evil words, and seek excuses in sins. |

Did you ever watch an altar boy squirm as he knelt on the steps of the altar? There were no altar girls in those days but the modern altar girl appears to be squirm-free. Perhaps she, like her mother, is biologically better equipped to endure pain and suffering than her male counterpart. The Latin Mass was a long Mass and there was no sitting down on weekdays. Mrs. O’Brien could kneel, sit, stand, or lie down, but the altar boy had no choice. There were brief moments when he could stand or move around but, mostly, he had to kneel. Hours and hours of kneeling. Sitting on the altar steps was a mortal sin and Fr. McCabe wasn’t blind. All the altar boy could do to relieve the back pain and the cramp in his thighs was to attempt some rather limited aerobics – otherwise known as squirming.

| Crucifixus etiam pro nobis. | He was crucified also for us. |

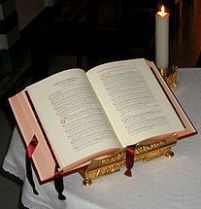

It wasn’t all pain and discomfort, though. There were some plum jobs for our altar boy. One of them was ringing the altar bell, or bells, as there were four small bells that tinkled together when shaken – and he had a lot of ringing to do. The most important bell-ringing occurred at the consecration. The altar boy had to kneel just behind the priest and ring the bells six times while holding up the end of the chasuble as the priest genuflected – to make sure that he didn’t catch his heel in it and fall over, he supposed. Other plum jobs were swinging the thurible so hard that Fr. McCabe disappeared in the fog; dowsing the tall candles high up on the altar; carrying the processional cross at the head of the posse; minding the priest’s biretta; and transferring the big missal.

The missal job was the plummiest job of all, and the most perilous. At that time the priest said Mass facing the high altar with his back to the congregation. Immediately before the gospel, the altar boy had to walk up the altar steps, pick up the big missal complete with brass stand, walk back down the steps, genuflect, and walk up the steps again to deposit the missal and stand on the other side of the altar, thus transferring them from the “epistle” side to the “gospel” side – something that the priest could do himself in two seconds. After Communion, they had to be transferred back where they came from.

The combination of missal and stand weighed a ton-and-a-half so that the altar boy had his work cut out just to carry them, never mind do pirouettes with them. But it all added to the spectacle. In addition, the same altar boy couldn’t see over the top of the missal but had to try to peer around it. His moment of true glory came when, staggering under the missal and unable to see where he was going, he kicked the undeserving altar bells from the top step down through the altar rails and into the aisle. Fortunately, Mrs. O’Brien was absent so the church was empty save for Fr. McCabe, who heard and saw nothing, and the tearful altar boy, who never told anyone.

| Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. |

Through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault. |

The job that was the second favourite of the unfortunate altar boy was carrying the processional cross − the crucifix mounted at the top of a longish pole. Whenever there was a procession out and around the church and back, or when the priest and whoever else were to be led on and off the altar, the proud little altar boy would be there in the van, carrying his cross. A plum job all right, but pride goes before a fall, and how great was his fall. He dozed off during Benediction. The priest’s footsteps woke him with a start and he jumped up immediately, took up his cross, and made a bee-line down the aisle through a sea of smiling faces. But the priest had merely stepped into the pulpit while the altar boy had stepped outside into the rain. What to do now? He wanted to go straight home but didn’t relish cycling in his cassock and cotta armed with the processional cross, like a knight on horseback. He did the only thing he could do and walked ignominiously back up the long aisle, his glowing ears lighting the way, to his place on the altar, with eyes riveted to the floor.

| In spiritu humilitatis et in animo contrito suscipiamur a te, Domine. |

In the spirit of humility and with a contrite heart receive us, O Lord. |

At that time there was a terrible lot of bowing, genuflecting, kissing of cruets, inclining towards the priest or the crucifix, bowing low during the Confiteor, and so on, which our altar boy was careful to learn by heart. He was very careful, also, to avoid touching the chalice or the ciborium. That was a special kind of sin that was neither mortal nor venial. It did not “kill the soul and deserve hell” but it severely wounded it and deserved a severe chastisement from Fr. Crowe, the parish priest, who was very sticky about that kind of thing. Fr. McCabe was too old to worry about such sacrileges, which was just as well for his shaking hand was the cause of a moral crisis in the conscience of his altar boy when the chalice he was offering him touched the boy’s thumb. Now, the thumb had not touched the chalice – it was the shaking chalice that had touched the thumb, or so the boy reasoned. There was no need, therefore, to genuflect, bow his head to the floor, and turn a cartwheel, or so he reasoned. So he did none of those. But he did not sleep well that night.

| Lavabo inter innocentes manus meas. Ne perdas cum impiis, Deus, animam meam. |

I will wash my hands among the innocent. Take not away my soul, O God, with the wicked. |

Holy Communion was a different affair in those days. There was no receiving the body of Christ in the hand but only on the tongue, and everyone knelt down at the altar rails. What of the altar boy? His job was to go before the priest with the paten or communion plate which he held under the chin of each communicant in turn, in case the host or some particles of it might fall. If that were to happen he would be unlikely to catch them for his attention was invariably on the different sizes and shapes of mouths, tongues, and teeth that were presented. That was on a Sunday when there were lots of tongues. They were a constant source of amusement for him and he was sometimes tempted to poke a finger into a gaping mouth – but he never did, or so he claimed.

| et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. |

and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. |

The end of Communion signalled the approach of the end of Mass and the end of squirming for the weary altar boy. There was only the reading from St. John’s gospel, the last Gospel, to get through and a few short prayers and then Mass would be over. At Sunday Mass this was the time of the quick getaway when those who had affairs that couldn’t wait caused a minor commotion at the back of the church. Of course, Fr. McCabe couldn’t hear it, but he new it was going on and he would creak round and glower at the backs of the faithful departing, to the delight of the faithful remaining. At midweek Mass it was a quiet time when our altar boy could reflect on his performance with satisfaction or regret.

| Ite, Missa est. | Go, the Mass is ended. |

At last, Fr. McCabe and his altar boy would stand side by side at the foot of the altar and bless themselves. The boy would genuflect and hand the biretta to the priest. The priest would perform a genuflection of desire and follow the boy off the altar. One day, Fr. McCabe didn’t comes back to his altar and, one day, neither did the altar boy.