First Confession

by

Frank O’Connor

All the trouble began when my grandfather died and my grand-mother – my father’s mother – came to live with us. Relations in the one house are a strain at the best of times but, to make matters worse, my grandmother was a real old countrywoman and quite unsuited to the life in town. She had a fat, wrinkled old face and, to Mother’s great indignation, went round the house in bare feet – the boots had her crippled, she said. For dinner she had a jug of porter and a pot of potatoes with, sometimes, a bit of salt fish, and she poured out the potatoes on the table and ate them slowly, with great relish, using her fingers by way of a fork.

Now, girls are supposed to be fastidious, but I was the one who suffered most from this. Nora, my sister, just sucked up to the old woman for the penny she got every Friday out of the old-age pension – a thing I could not do. I was too honest, that was my trouble, and when I was playing with Bill Connell, the sergeant-major’s son, and saw my grandmother steering up the path with the jug of porter sticking out from beneath her shawl, I was mortified. I made excuses not to let him come into the house because I could never be sure what she would be up to when we went in.

When Mother was at work and my grandmother made the dinner I wouldn’t touch it. Nora once tried to make me but I hid under the table from her and took the bread-knife with me for protection. Nora let on to be very indignant (she wasn’t, of course, but she knew Mother saw through her, so she sided with Gran) and came after me. I lashed out at her with the bread-knife and, after that, she left me alone. I stayed there till Mother came in from work and made my dinner, but when Father came in later, Nora said in a shocked voice, “Oh, Dadda, do you know what Jackie did at dinnertime?” Then, of course, it all came out. Father gave me a flaking, Mother interfered, and for days after that he didn’t speak to me and Mother barely spoke to Nora.

And all because of that old woman! God knows, I was heart-scalded. Then, to crown my misfortunes, I had to make my first confession and communion. It was an old woman called Ryan who prepared us for these. She was about the one age with Gran. She was well-to-do, lived in a big house on Montenotte, wore a black cloak and bonnet, and came every day to school at three o’clock when we should have been going home, and talked to us of hell. She may have mentioned the other place as well, but that could only have been by accident, for hell had the first place in her heart.

She lit a candle, took out a new half-crown, and offered it to the first boy who would hold one finger – only one finger! – in the flame for five minutes by the school clock. Being always very ambitious I was tempted to volunteer, but I thought it might look greedy. Then she asked were we afraid of holding one finger – only one finger! – in a little candle flame for five minutes and not afraid of burning all over in roasting hot furnaces for all eternity. All eternity! Just think of that! A whole lifetime goes by and it’s nothing, not even a drop in the ocean of your sufferings. The woman was really interesting about hell, but my attention was all fixed on the half-crown. At the end of the lesson she put it back in her purse. It was a great disappointment. A religious woman like that, you wouldn’t think she’d bother about a thing like a half-crown.

Another day she said she knew a priest who woke one night to find a fellow he didn’t recognise leaning over the end of his bed. The priest was a bit frightened, naturally enough, but he asked the fellow what he wanted and the fellow said in a deep, husky voice that he wanted to go to confession. The priest said it was an awkward time and wouldn’t it do in the morning, but the fellow said that last time he went to confession, there was one sin he kept back, being ashamed to mention it, and now it was always on his mind. Then the priest knew it was a bad case because the fellow was after making a bad confession and committing a mortal sin. He got up to dress, and just then the cock crew in the yard outside, and lo and behold! – when the priest looked round there was no sign of the fellow, only a smell of burning timber, and when the priest looked at his bed didn’t he see the print of two hands burned in it? That was because the fellow had made a bad confession. This story made a shocking impression on me.

But the worst of all was when she showed us how to examine our conscience. Did we take the name of the Lord, our God, in vain? Did we honour our father and our mother? (I asked her did this include grandmothers and she said it did.) Did we love our neighbours as ourselves? Did we covet our neighbour’s goods? (I thought of the way I felt about the penny that Nora got every Friday.) I decided that, between one thing and another, I must have broken the whole ten commandments, all on account of that old woman and, so far as I could see, so long as she remained in the house I had no hope of ever doing anything else.

I was scared to death of confession. The day the whole class went I let on to have a toothache, hoping my absence wouldn’t be noticed but, at three o’clock, just as I was feeling safe, along comes a chap with a message from Mrs. Ryan that I was to go to confession myself on Saturday and be at the chapel for communion with the rest. To make it worse, Mother couldn’t come with me and sent Nora instead.

Now, that girl had ways of tormenting me that Mother never knew of. She held my hand as we went down the hill, smiling sadly and saying how sorry she was for me, as if she were bringing me to the hospital for an operation.

“Oh, God help us!” she moaned. “Isn’t it a terrible pity you weren’t a good boy? Oh, Jackie, my heart bleeds for you! How will you ever think of all your sins? Don’t forget you have to tell him about the time you kicked Gran on the shin.”

“Lemme go!” I said, trying to drag myself free of her. “I don’t want to go to confession at all.”

“But sure, you’ll have to go to confession, Jackie!” she replied in the same regretful tone. “Sure, if you didn’t, the parish priest would be up to the house, looking for you. Tisn’t, God knows, that I’m not sorry for you. Do you remember the time you tried to kill me with the bread-knife under the table? And the language you used to me? I don’t know what he’ll do with you at all, Jackie. He might have to send you up to the bishop.”

I remember thinking bitterly that she didn’t know the half of what I had to tell if I told it. I knew I couldn’t tell it, and understood perfectly why the fellow in Mrs. Ryan’s story made a bad confession. It seemed to me a great shame that people wouldn’t stop criticising him. I remember that steep hill down to the church, and the sunlit hillsides beyond the valley of the river, which I saw in the gaps between the houses like Adam’s last glimpse of Paradise.

Then, when she had manoeuvred me down the long flight of steps to the chapel yard, Nora suddenly changed her tone. She became the raging malicious devil she really was.

“There you are!” she said with a yelp of triumph, hurling me through the church door. “And I hope he’ll give you the penitential psalms, you dirty little caffler.”

I knew then I was lost, given up to eternal justice. The door with the coloured-glass panels swung shut behind me, the sunlight went out and gave place to deep shadow, and the wind whistled outside so that the silence within seemed to crackle like ice under my feet. Nora sat in front of me by the confession box. There were a couple of old women ahead of her, and then a miserable-looking poor devil came and wedged me in at the other side so that I couldn’t escape even if I had the courage. He joined his hands and rolled his eyes in the direction of the roof, muttering aspirations in an anguished tone, and I wondered had he a grandmother too. Only a grandmother could account for a fellow behaving in that heartbroken way, but he was better off than I, for he at least could go and confess his sins while I would make a bad confession and then die in the night and be continually coming back and burning people’s furniture.

Nora’s turn came, and I heard the sound of something slamming, and then her voice as if butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth, and then another slam, and out she came. God, the hypocrisy of women! Her eyes were lowered, her head was bowed, and her hands were joined very low down on her stomach, and she walked up the aisle to the side altar looking like a saint. You never saw such an exhibition of devotion; and I remembered the devilish malice with which she had tormented me all the way from our door, and wondered were all religious people like that, really.

It was my turn now. With the fear of damnation in my soul I went in, and the confessional door closed of itself behind me. It was pitch-dark and I couldn’t see priest or anything else. Then I really began to be frightened. In the darkness it was a matter between God and me, and He had all the odds. He knew what my intentions were before I even started. I had no chance. All I had ever been told about confession got mixed up in my mind, and I knelt to one wall and said, “Bless me, father, for I have sinned. This is my first confession.” I waited for a few minutes but nothing happened, so I tried it on the other wall. Nothing happened there either. He had me spotted all right.

It was my turn now. With the fear of damnation in my soul I went in, and the confessional door closed of itself behind me. It was pitch-dark and I couldn’t see priest or anything else. Then I really began to be frightened. In the darkness it was a matter between God and me, and He had all the odds. He knew what my intentions were before I even started. I had no chance. All I had ever been told about confession got mixed up in my mind, and I knelt to one wall and said, “Bless me, father, for I have sinned. This is my first confession.” I waited for a few minutes but nothing happened, so I tried it on the other wall. Nothing happened there either. He had me spotted all right.

It must have been then that I noticed the shelf at about one height with my head. It was really a place for grown-up people to rest their elbows, but in my distracted state I thought it was probably the place you were supposed to kneel. Of course, it was on the high side and not very deep, but I was always good at climbing and managed to get up all right. Staying up was the trouble. There was room only for my knees, and nothing you could get a grip on but a sort of wooden moulding a bit above it. I held on to the moulding and repeated the words a little louder, and this time something happened all right. A slide was slammed back, a little light entered the box, and a man’s voice said, “Who’s there?”

“‘Tis me, father,” I said, for fear he mightn’t see me and go away again. I couldn’t see him at all. The place the voice came from was under the moulding, about level with my knees, so I took a good grip of the moulding and swung myself down till I saw the astonished face of a young priest looking up at me. He had to put his head on one side to see me, and I had to put mine on one side to see him, so we were more or less talking to one another upside-down. It struck me as a queer way of hearing confessions, but I didn’t feel it my place to criticise.

“Bless me, father, for I have sinned. This is my first confession”, I rattled off all in one breath, and swung myself down the least shade more to make it easier for him.

“What are you doing up there?” he shouted in an angry voice, and the strain the politeness was putting on my hold of the moulding, and the shock of being addressed in such an uncivil tone, were too much for me. I lost my grip, tumbled, and hit the door an unmerciful wallop before I found myself flat on my back in the middle of the aisle. The people who had been waiting stood up with their mouths open. The priest opened the door of the middle box and came out, pushing his biretta back from his forehead. He looked something terrible.

Then Nora came scampering down the aisle. “Oh, you dirty little caffler!” she said. “I might have known you’d do it. I might have known you’d disgrace me. I can’t leave you out of my sight for one minute.” Before I could even get to my feet to defend myself she bent down and gave me a clip across the ear. This reminded me that I was so stunned I had even forgotten to cry so that people might think I wasn’t hurt at all when, in fact, I was probably maimed for life. I gave a roar out of me.

“What’s all this about?” the priest hissed, getting angrier than ever and pushing Nora off me. “How dare you hit the child like that, you little vixen?”

“But I can’t do my penance with him, father”, Nora cried, cocking an outraged eye up at him.

“Well, go and do it, or I’ll give you some more to do”, he said, giving me a hand up. “Was it coming to confession you were, my poor man?” he asked me.

“‘Twas, father”, said I with a sob.

“Oh”, he said respectfully, “a big hefty fellow like you must have terrible sins. Is this your first?”

“‘Tis, father”, said I.

“Worse and worse”, he said gloomily. “The crimes of a lifetime. I don’t know will I get rid of you at all today. You’d better wait now till I’m finished with these old ones. You can see by the looks of them they haven’t much to tell.”

“I will, father”, I said with something approaching joy.

The relief of it was really enormous. Nora stuck out her tongue at me from behind his back, but I couldn’t even be bothered retorting. I knew from the very moment that man opened his mouth that he was intelligent above the ordinary. When I had time to think I saw how right I was. It only stood to reason that a fellow confessing after seven years would have more to tell than people that went every week. The crimes of a lifetime, exactly as he said. It was only what he expected, and the rest was the cackle of old women and girls with their talk of hell, the bishop, and the penitential psalms. That was all they knew. I started to make my examination of conscience and, barring the one bad business of my grandmother, it didn’t seem so bad.

The next time, the priest steered me into the confession box himself and left the shutter back, the way I could see him get in and sit down at the further side of the grille from me.

“Well, now”, he said, “what do they call you?”

“Jackie, father”, said I.

“And what’s a-trouble to you, Jackie?”

Father”, I said, feeling I might as well get it over while I had him in good humour, “I had it all arranged to kill my grandmother.”

He seemed a bit shaken by that, all right, because he said nothing for quite a while.

“My goodness”, he said at last, “that’d be a shocking thing to do. What put that into your head?”

Father”, I said, feeling very sorry for myself, “she’s an awful woman”.

“Is she?” he asked. “What way is she awful?”

“She takes porter, father”, I said, knowing well from the way Mother talked of it that this was a mortal sin, and hoping it would make the priest take a more favourable view of my case.

“Oh, my!” he said, and I could see he was impressed.

“And snuff, father”, said I.

“That’s a bad case, sure enough, Jackie,” he said.

“And she goes round in her bare feet, father”, I went on in a rush of self-pity, “and she knows I don’t like her, and she gives pennies to Nora and none to me, and my da sides with her and flakes me, and one night I was so heart-scalded I made up my mind I’d have to kill her.”

“And what would you do with the body?” he asked with great interest.

“I was thinking I could chop that up and carry it away in a barrow I have”, I said.

“Begor, Jackie”, he said, “do you know you’re a terrible child?”

“I know, father”, I said, for I was just thinking the same thing myself. “I tried to kill Nora too with a bread-knife under the table, only I missed her.”

“Is that the little girl that was beating you just now?” he asked.

“‘Tis, father.”

“Someone will go for her with a bread-knife one day, and he won’t miss her”, he said rather cryptically. “You must have great courage. Between ourselves, there’s a lot of people I’d like to do the same to, but I’d never have the nerve. Hanging is an awful death.”

“Is it, father?” I asked with the deepest interest – I was always very keen on hanging. “Did you ever see a fellow hanged?”

“Dozens of them”, he said solemnly. “And they all died roaring.”

“Jay!” I said.

“Oh, a horrible death!” he said with great satisfaction.

“Lots of the fellows I saw killed their grandmothers too, but they all said ’twas never worth it.”

He had me there for a full ten minutes talking, and then walked out the chapel yard with me. I was genuinely sorry to part with him, because he was the most entertaining character I’d ever met in the religious line. Outside, after the shadow of the church, the sunlight was like the roaring of waves on a beach. It dazzled me and when the frozen silence melted and I heard the screech of trams on the road, my heart soared. I knew now I wouldn’t die in the night and come back leaving marks on my mother’s furniture. It would be a great worry to her, and the poor soul had enough.

Nora was sitting on the railing, waiting for me, and she put on a very sour puss when she saw the priest with me. She was mad jealous because a priest had never come out of the church with her.

“Well”, she asked coldly, after he left me, “what did he give you?”

“Three Hail Marys”, I said.

“Three Hail Marys”, she repeated incredulously. “You mustn’t have told him anything.”

“I told him everything”, I said confidently.

“About Gran and all?”

“About Gran and all.”

(All she wanted was to be able to go home and say I’d made a bad confession.)

“Did you tell him you went for me with the bread-knife?” she asked with a frown.

“I did to be sure.”

“And he only gave you three Hail Marys?”

“That’s all.”

She slowly got down from the railing with a baffled air. Clearly, this was beyond her. As we mounted the steps back to the main road, she looked at me suspiciously.

“What are you sucking?” she asked.

“Bullseyes.”

“Was it the priest gave them to you?”

“‘Twas.”

“Lord God”, she wailed bitterly, “some people have all the luck! ‘Tis no advantage to anybody trying to be good. I might just as well be a sinner like you.”

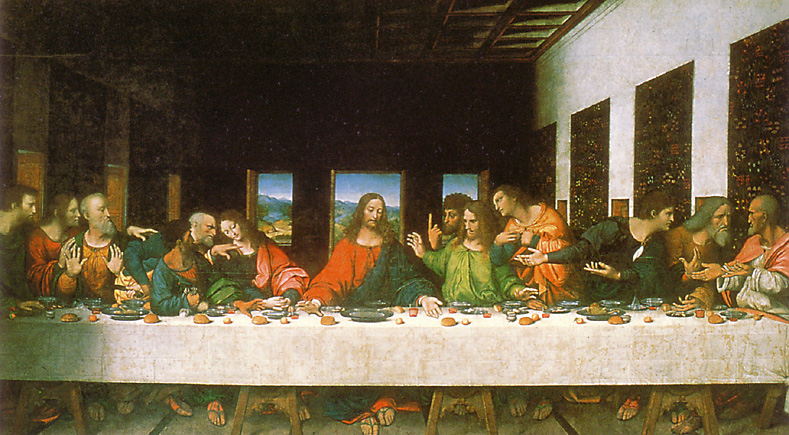

Matrimony, or marriage, is a covenant between a man and a woman by which they establish between themselves a partnership for the whole of life. For a valid marriage, a man and a woman must express their conscious and free consent to a definitive self-giving to each other. It is ordinarily celebrated in a nuptial Mass. For much of the Church’s history, no specific ritual was prescribed for celebrating a marriage: Marriage vows did not have to be exchanged in a church, nor was a priest’s presence required. A couple could exchange consent anywhere, anytime.

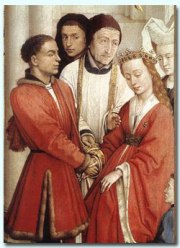

Matrimony, or marriage, is a covenant between a man and a woman by which they establish between themselves a partnership for the whole of life. For a valid marriage, a man and a woman must express their conscious and free consent to a definitive self-giving to each other. It is ordinarily celebrated in a nuptial Mass. For much of the Church’s history, no specific ritual was prescribed for celebrating a marriage: Marriage vows did not have to be exchanged in a church, nor was a priest’s presence required. A couple could exchange consent anywhere, anytime. On the right is another detail from the Seven Sacraments painting. Can you find the detail in the full picture?

On the right is another detail from the Seven Sacraments painting. Can you find the detail in the full picture?

Priests depend on their bishops in the exercise of their pastoral functions – they are called to be the bishops’ prudent co-workers. They receive from the bishop the charge of a parish community or some other office within the diocese.

Priests depend on their bishops in the exercise of their pastoral functions – they are called to be the bishops’ prudent co-workers. They receive from the bishop the charge of a parish community or some other office within the diocese. The transitional diaconate is a temporary stage which a man passes through on his way to be ordained to the priesthood. Normally, a transitional deacon is ordained as a priest after six months.

The transitional diaconate is a temporary stage which a man passes through on his way to be ordained to the priesthood. Normally, a transitional deacon is ordained as a priest after six months.